Have you ever tried to cancel a subscription and ended up in a never-ending loop? Or clicked “No” only to be guilted into saying yes? These are not UX bugs. They’re features. Intentionally deceptive ones. Welcome to the world of dark patterns.

What are dark patterns?

Dark patterns can be defined as “practices or deceptive design pattern using user interface or user experience interactions on any platform that is designed to mislead or trick users to do something they originally did not intend or want to do, by subverting or impairing the consumer autonomy, decision making or choice, amounting to misleading advertisement or unfair trade practice or violation of consumer rights.”

Wait, what do you mean? Basically – dark patterns are design practices in websites or apps that intentionally trick or manipulate users into making decisions they wouldn’t otherwise make – like buying something, sharing personal data, or signing up for a service.

The term was coined by Harry Brignull – to communicate the unscrupulous nature of such patterns, and also the fact that it can be shadowy and hard to pin down. Governments around the world – including India – are now catching up to this shady side of digital design.

What are some identified dark patterns in India?

| Dark Pattern | Example | Explanation |

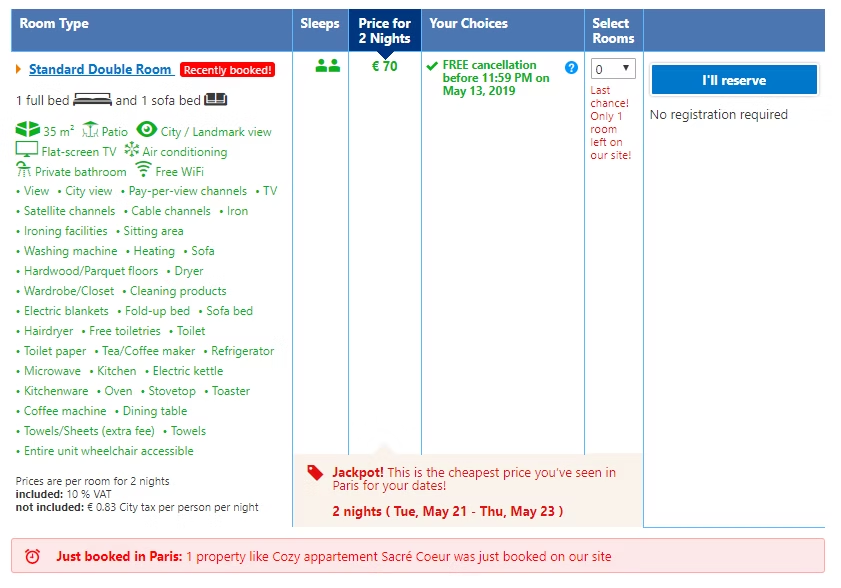

| False urgency | A hotel booking site shows “Only 2 rooms left!” when actually dozens are available. | Misleads users into rushing a decision based on a non-existent scarcity — unlawful pressure tactic. |

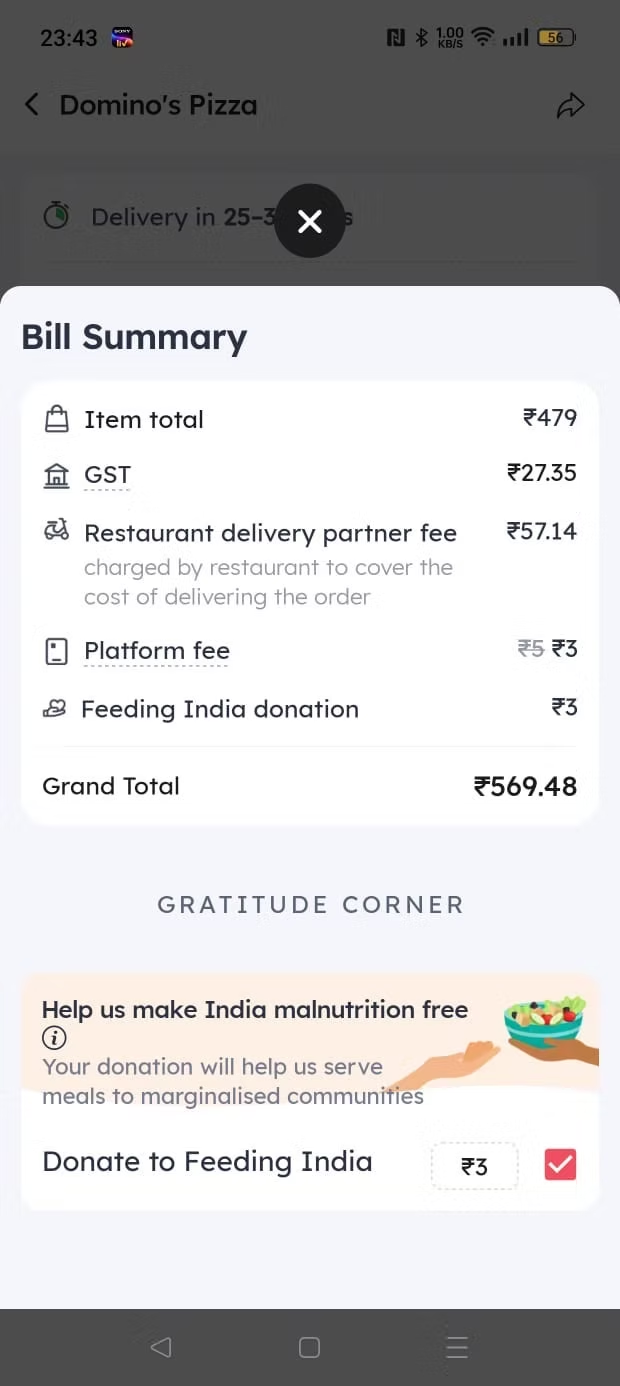

| Basket sneaking | E‑commerce checkout auto‑adds a small “donation to charity” via pre‑checked box. | Adds extra cost without explicit consent, relying on user inattention. |

| Confirm shaming | A flight site asks “Skip travel insurance? I’ll be irresponsible” in the opt‑out button. | Uses guilt/shame to manipulate user choice. |

| Forced action | Health site forces newsletter signup before allowing purchase of vitamins. | Makes unrelated promotion compulsory to complete a transaction. |

| Subscription trap | OTT platform hides subscription cancellation behind email & phone request. | Cancelling is made deliberately harder than subscribing. |

| Interface interference | “No” button in app pop-up is faint/unreadable, while “Yes” is bright and prominent. | UI design nudges users toward a specific choice. |

| Bait and switch | “Download premium anniversary offer!” — but at final step, it’s a higher‑priced plan. | Promises one thing but delivers another at checkout. |

| Drip pricing | Flight ticket listed at ₹3,000 — but at checkout add ₹800 in “service fees” not previously shown. | Hides full cost until late in the purchase process. |

| Disguised advertisement | A blog post shows “user review” box which is in fact a paid placement. | Ads are disguised as authentic user-generated content. |

| Nagging | News app repeatedly prompts “Enable notifications” every time user opens it. | Repetitive pop-ups push users toward unwanted actions. |

| Trick question | Checkbox reads: “Uncheck if you don’t want to stop receiving offers” — double negatives confuse users. | Confusing language leads to unintended consent. |

| SaaS billing | Free trial ends and auto-converts to paid monthly plan without notifying a user. | Continues charging without alerting the user. |

| Rogue malware | Scareware popup on a download site claims your PC is infected and urges purchase of fake antivirus. | Tricks users into installing malware disguised as a solution. |

Why do dark patterns work?

Dark patterns are effective because they take advantage of how our brains process information and make decisions. We are not always rational and logical when we interact with online platforms. We often rely on heuristics (mental shortcuts) that help us save time and effort, but can also lead us to errors and biases. For example:

- Availability: We tend to judge the likelihood of events based on how easily we can recall examples from memory. For example, we might think that a product is popular or high-quality if we see many positive reviews or ratings, even if they are fake or biased.

- Anchoring: We tend to rely too much on the first piece of information we see when making judgments. For example, we might think that a product is a good deal if it is marked down from a high original price, even if the original price was inflated or arbitrary.

- Confirmation Bias: We tend to seek out and favor information that confirms our existing beliefs and opinions. For example, we might ignore or dismiss negative reviews or ratings of a product that we already like or want to buy.

- Loss Aversion: We tend to prefer avoiding losses over acquiring gains of equal value. For example, we might be more likely to buy a product if we are told that we will lose a discount or a free trial if we don’t act soon.

- Reciprocity: We tend to feel obliged to return favors or gifts that are given to us. For example, we might be more likely to sign up for a newsletter or a subscription if we are offered a free ebook or a trial period.

By leveraging these psychological tendencies, dark patterns can nudge users into decisions that feel natural in the moment – but aren’t necessarily in their best interest.

How is India dealing with dark patterns?

Guidelines for Prevention and Regulation of Dark Patterns, 2023

In November 2023, India became one of the first countries to formally recognize and ban dark patterns through the Guidelines for Prevention and Regulation of Dark Patterns, 2023 [“Guidelines”] issued by the Department of Consumer Affairs. These were backed by the Consumer Protection Act, 2019 [“CPA”], which prohibits unfair trade practices. The abovementioned 13 specific dark patterns are identified in the Indian guidelines. These dark patterns are now considered “unfair trade practices” under Section 2(47) of the CPA, and can attract penalties from the Central Consumer Protection Authority [“CCPA”]. As per Section 3 of the Guidelines, all (i) platforms that are systematically offering goods or services in India, (ii) advertisers, and (iii) sellers are covered under these Guidelines. Interestingly, the Jagriti app, along with the Jago Grahak Jago app and Jagriti Dashboard, are tools launched by the Department of Consumer Affairs to combat dark patterns and protect consumers. The Jagriti app specifically allows users to report websites or e-commerce platforms that they suspect are using dark patterns, which are then investigated by the CCPA.

The DPDP Act, 2023

While the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 [“DPDP Act“] doesn’t mention “dark patterns” by name, it contains several provisions that implicitly outlaw them. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 focuses heavily on ensuring that personal data is processed only after obtaining valid consent from users.

Under Section 6(1) of the DPDP Act, consent must be free, specific, informed, unconditional and unambiguous. This means users must clearly know what they’re agreeing to – and cannot be misled, forced, or manipulated. Dark patterns such as pre-selected checkboxes, “accept all” popups without alternatives, or vague privacy options fall afoul of this requirement. If a user is tricked into giving consent, that consent is invalid under the DPDP Act.

Section 6(5) of the Act requires that withdrawing consent be as easy as it was to give. This is a direct counter to the “roach motel” pattern, where users can easily sign up but can’t figure out how to unsubscribe or revoke access. The DPDP Act demands that platforms offer a straightforward, visible way to opt out. Burying unsubscribe links under layers of menus or making users email support to delete their account will no longer be acceptable.

Section 5(2) of the Act mandates that notices be given in clear and plain language. This means no more walls of legalese, vague clauses, or hidden disclosures. Users must be able to read and comprehend how their data will be used, by whom, and for what purpose. Dark patterns often rely on confusing, overwhelming notices to slide questionable practices past the user – something this clause seeks to prevent.

Section 6(2) of the Act restricts data processing only for the purpose consented to by the user. This strikes at the heart of another dark pattern – bundled or forced consent. For instance, if an app asks for access to your location “to personalize your feed” but also uses it for ad tracking, that’s a violation. Users must consent to each purpose separately and clearly, and companies cannot hide behind vague catch-all terms like “service improvement.”

Therefore, even without saying the words “dark patterns,” the DPDP Act provides strong legal protections against them. By focusing on meaningful consent, purpose limitation, clarity, and ease of withdrawal, the Act effectively outlaws the most common manipulative UX strategies.

IT Rules, 2021

Though the Information Technology Act, 2000 [“IT Act”], India’s foundational cyber law, does not explicitly refer to dark patterns, it contains certain provisions – especially through the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 [“2021 Rules”] that can be interpreted to address these deceptive practices.

Deceptive design may violate Rule 3(1)(a), which requires that intermediaries ensure users do not host or transmit content that is deceptive or misleading in nature. While this was originally meant to tackle misinformation and fraud, it can be interpreted to cover UI-based deception – such as misleading subscription flows, fake urgency timers, or misdirection through color and placement. When a design tricks a user into giving consent or making a purchase unintentionally, it arguably becomes “misleading.”

SSMIs – platforms with over 50 lakh registered users – have additional obligations, such as publishing terms of use in clear language, allowing voluntary user verification, providing controls for privacy and content visibility. If these privacy controls are buried, confusing, or hard to access, that could violate both the letter and spirit of these rules. Platforms that hide opt-out settings or trick users into consenting to broad data use could be scrutinized for failing their duty of transparency.

The 2021 Rules also have due diligence obligations under Rule 3(1)(b). This clause requires platforms to exercise due diligence to ensure their services aren’t used in ways that are unethical or illegal. If the platform itself employs deceptive UX design to drive up engagement, data collection, or purchases, that could be seen as a failure of due diligence.

Dark patterns not only deceive users – they potentially create a misleading digital environment, which these rules were designed to prevent.

ASCI

The Advertising Council of India [“ASCI”] is a self-regulatory organization for the advertising industry to protect the interest of consumers against false and misleading advertisements. ASCI is increasingly stepping into the space of dark patterns, particularly in the context of digital advertising and influencer marketing, where manipulative tactics are often deployed to mislead consumers. In November 2022, the ASCI released a discussion paper highlighting various kinds of dark patterns being used by digital platforms to manipulate consumer’s choices and patterns. Subsequently, in June 2023 the ASCI issued guidelines on Deceptive Design Patterns in India [“ASCI Guidelines”] to further the objective of the ASCI Code to ensure honesty from the advertiser and prevent the advertisers from taking advantage of vulnerable customers by any omission, exaggeration, implication, or ambiguity in the advertisements. The ASCI Guidelines talks about dark patterns like drip pricing, bait and switch, false urgency, and disguised ads.

What’s the recent update relating to enforcement of law against dark patterns?

On June 5, 2025, the CCPA issued an advisory under the CPA, calling on all e-commerce platforms operating in India to:

- Conduct a self-audit within 3 months to identify and eliminate dark patterns;

- Submit a public self-declaration of compliance;

- Ensure their platform’s design and consent mechanisms do not violate the Guidelines or the Consumer Protection (E-Commerce) Rules, 2020.

This advisory applies to all platforms offering goods or services online, regardless of sector – including food delivery apps, travel portals, e-commerce sites, ed-tech platforms, and digital marketplaces.

Effective from June 6, 2025, and valid through December 31, 2026, the advisory sets out a forward-looking framework for enhancing consumer protection in the digital economy. Although framed as an advisory, it functions as an extension of the existing Guidelines issued under the CPA, and thus carries enforceable weight.

Additionally, a Joint Working Group [“JWG“] has been formed by the Department of Consumer Affairs to monitor compliance and further action. The JWG includes representatives from relevant ministries, regulators, voluntary consumer organizations, and national law universities. This group is tasked with identifying violations of dark patterns, sharing findings regularly with the department, and suggesting awareness programs for consumers.

The Copy That! View

Dark patterns represent the dark side of digital design – one that undermines user trust, autonomy, and dignity. But India is moving quickly to push back. From hard law (Consumer Protection Act, DPDP Act) to platform governance (IT Rules), and soft law (ASCI self-regulation), a growing framework is emerging to prioritize user rights over manipulative engagement. The next step is enforcement, awareness, and business compliance. Digital players – big and small – must now ask themselves: “Are we designing for users… or designing around them?” Because the age of “caught in the click” may finally be coming to an end.